The goal of being culturally responsive as an educator is soemthing many among us aspire to, but there aren’t that many really clear approaches that just happen to be laying about.

We all have to find ways within our own context to align school goals with the goal or being culturally responsive. Indeed, D’Aietti et al., (2021) explores the really interesting approach taken between being ‘culturally responsive’ and also ‘explicit instruction’, noting the ways that these two approaches seem at odds; but exploring ways that they worked to resolve these conflicts within their own context. For many of us, similar though unique challenges are also present.

To lay the landscape of culturally responsive approaches within Australia, with a specific focus upon Indigenous Australian as the most threatened and difficult culture to respond to, I’ve selected some useful quotes from AITSLs overview report on the topic.

Beginning with a call to action it proclaims:

“The detrimental gaps apparent between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous peoples is a social justice issue. It is an economic issue. It is a political issue. Addressing this issue is not possible if change does not occur. Addressing this issue is only possible if teachers and the systems they work within are willing to make the necessary changes and reflect on themselves and their structures.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 2)

Now for the vast majority of teachers we can reflect on ourselves easily, and become more aware of the structures that we work within, working to ‘talk truth to power’ (Hill Collins, 2013) as a means to slowly alter them. It’s always best to make these changes from within the apparatus that needs changing, when and where that is possible.

They note that, “teachers sometimes interpret cultural competency as an imperative or assumption to teach culture. rather than simply teach about culture or facilitate culturally responsive learning experiences in collaboration with community.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 7). So it’s not necessary to be the final arbiter of all knowledge, but you have to be willing to open the conversations and be willing to share our points. I guess sit with awkwardness and trouble and content within your classroom. Might just be me but in my experience this is when teaching is at its most exciting. When teachers are engaging with the worlds of their students and those worlds of being brought into the classroom and made meaningful by interactions between students learning about the world.

Something that you will certainly experience as you explore culturally responsive approaches is that it requires at points to put strain upon an indigenous community around you. As they note, “Almost two-thirds of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander workers surveyed experience high 'identity strain' (a term coined by the research team) referring to feelings that they themselves, or others, view inner identity as not meeting the norms or expectations of the dominant culture in the workplace. The concept draws on literature demonstrating members of minority groups expend effort and energy managing their identity in the workplace to avoid the negative consequences of discrimination, harassment, bias and marginalisation.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 8).

So within these groups, there is a strain to remain within expected norms of the dominant group, but also I would add, the additional strain of well meaning adults seeking for these people to also share their culture and be representatives of it, mostly in ways that will benefit either those asking, or the organisation as a whole. So in essence, being asked to fit in, but also represent their identity in culturally acceptable ways - to ‘write the Reconciliation action plan, run the Indigenous connections program, and so much more - in addition to their core duties.

For us as teachers: “The importance of critical self-reflection was highlighted in all stages of the consultation process. Part of the reason for this is that while other factors such as relationship building, content, and pedagogical approach are seen as crucial, the cultural responsiveness of the teacher is ultimately a function of their worldview and implicit biases. These assumptions inform the way teachers bring processes of relationship building and pedagogy together.” (AITSL, 2022a, P. 10) In this respect, the Intercultural development self-reflection tool of AITSL (2022b) is a useful starting point, albeit not it’s mapped to the APSTs, which won’t be super familiar to most teachers, but locating a meaningful starting point for your further development in this facet of teaching is useful.

My results noted that: that I needed to engage with my own intercultural competence, though to be honest, I think this is mostly in response to the policies within the broader context, schools and policies. It noted that:

“Intercultural Competence is the ability to understand, interact and communicate with people from a background that is different to one’s own in ways that are sensitive to individual needs. It is developed through obtaining knowledge, skills and the appropriate attitudes and beliefs needed to interact with people from different backgrounds. This means valuing diverse cultural identities, knowledges and traditions and recognising the centrality of connections to family, community and the land to individual wellbeing.”

Considering the tool is called the ‘Intercultural development self-reflection tool’ this is rather a confusing result overall, but you know, a tool that tells you that you need to learn more and more is rather a self fulfilling property.

So that we might begin to start “Understanding personal identity: relates to the observed need for educators to be more self-aware, not just of their assumptions but their own personal identity that exists in culture. lo be aware that their identity and culture are bound together, and that they bring this identity into their understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 23). So in short, you are not an absence of culture, you are rich with culture, assumptions and beliefs, that shape the way you view students, other teachers and teaching itself.

A neat submission noted that:

"There needs to be an ability and openness to see the big picture and the willingness to share, to listen and to learn. Individuals should have a strong sense of their own personal identity and story, recognising how important this is for others.' (Submission 36)”

(AITSL, 2022, P. 11). Which is a reasonable thing that I need to work on.

Something id not heard of until recently is, “A Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) is a formal statement of commitment to reconciliation and Reconciliation Australia's Narragunnawali platform provides a practical framework for schools and early learning services to genuinely engage in processes of reconciliation. Even where RAPs were not explicitly referenced, many more proposed solutions forward in the submissions can also clearly be mapped to one or more RAP actions.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 16). So by engaging in the process of becoming culturally responsive - you are also working towards completing elements of a Reconciliation Action Plan, even if you didn’t know this was a thing.

As a group, “The consultation process highlighted that there is still much to do to improve teacher capability to embed Indigenous perspectives. To this end, professional learning and access to appropriate teaching and learning resources are vitally important as is the implementation of culturally responsive pedagogy . The upcoming introduction of Version 9.0 of the Australian Curriculum will be an important time to explore how to best support teachers to deliver on all areas of the curriculum holistically and in a culturally respectful manner.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 17). This is a hopeful framing, but it seems as likely as anything to make a change, to be honest.

The goal is to “embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content and perspectives across all learning areas through ACARA's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority. Such concerns also extended to practicums and the knowledge and understanding of supervising teachers.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 19). Which is a massive issue, I’ve personally gotten to this standard when supervising teachers and shrugged, because on practicum such short stints are in place that it’s hard to get happening along with their many other concerns during these times.

What’s needed is “authentic resources that align to the curriculum to develop their own cultural responsiveness and ensure they are delivering culturally diverse and responsive content to their students.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 20). This is something that I’ve begun working on and towards.

And also, PL, “Similar concerns were noted about professional learning options. To develop cultural responsiveness, the written submissions highlighted that schools and education systems and sectors must invest sufficient funding to support evidence-based professional learning for all teaching staff. Anti-racism, cultural awareness, and racial literacy and tolerance were identified as essential topics for professional learning for the Australian teaching workforce.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 21). There is a dearth of good PL overall, but also a massive gap in culturally responsive approaches. “Furthermore. it was emphasised that professional learning relating to the development of cultural responsiveness needed to be part or an ongoing rather than a once-off component or a schools of region's professional learning program/schedule.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 21). Which in my experience is true, maybe once a year tops we turn to these matters.

We need to have some decent:

“•Content: refers to descriptions of cultural responsiveness characterised as the presence of artifacts, such as flags, signs in the local language, or information about culture / history. These elements were often described in absence of any discussion of pedagogy.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 22)

But more to the point:

“Pedagogy: refers to the use of culturally responsive pedagogies (both inside and outside the classroom) e.g.: yarning circles; involvement of families; practical hands-on activities. These practices were appropriate to a students but soon as distinct from the mainstream.” (AITSL, 2022, P. 22). As I’ve been advocating for, for a little while at least.

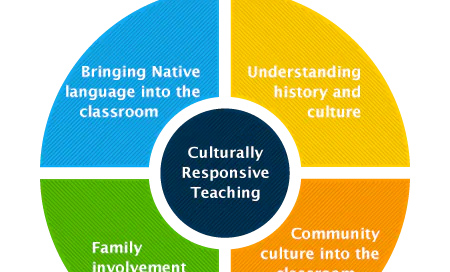

Among the themes within the report, the below graph is useful:

Lots to learn, lots to develop, and lots of gaps - but something meaningful for us to explore.

References

AITSL (2022a) Building a culturally responsive australian teaching workforce. Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, June 2022, report.

AITSL (2022b) Intercultural development capability framework. Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership.

AITSL (2022c) Intercultural development self-reflection tool. Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership.

D'Aietti, K., Lewthwaite, B., & Chigeza, P. (2021). Negotiating the pedagogical requirements of both explicit instruction and culturally responsive pedagogy in Far North Queensland: teaching explicitly, responding responsively. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50(2), 312-319.

Hill Collins, P. (2013). Truth-telling and intellectual activism. Contexts, 12(1), 36-41.

Running Word Count (the second 100,000): 17,234