How to challenge status quo within Teaching

Two primary ways

Here id like to explore ‘circling the square’ as a compelling metaphor for challenging the academic approach with a form of ‘intellectual activism’ (Hill Collins, 2013; Hogarth,2021). Also applies neatly to the teaching profession itself, where many of the workers within the system are intellectuals, atleast to a certain extent. And as activists we are looking to install a sense of ‘organic intellectualism’ (Gramsci, 1971) among the teaching profession. This context makes the softening of structures and the challenging of dominant narratives important in a profession where ideas are the commodities we traffic.

Hill Collins (2013) outlines two clear ways that we might carry our intellectual activism, by speaking truth to power; and by speaking the truth to the people. As teachers these are both equally challenging, power because much of the downward communication within a school occurs in bulk, via one-sided address and stable, flat professional learning delivery.

As Patricia notes,

“My lengthy educational training was designed to equip me to wield the language of power to serve the interests of the gatekeepers who granted me legitimacy.” (Hill Collins, 2013, Pp.37) Whether we realise this or not, this is the core issue of teaching, at the current state, it is those most formed by the formative culture of education, rather than necessarily the calling to improve society that can be suggested as the largest pull. This means that the most dedicated student becomes the most dedicated student, and it is the 3 or 4 years of university where they are almost required to be radicalised if we ever hope to change their persons, so that we might change the system.

Adding that,

“Speaking the truth to power in ways that undermine and challenge that power is often best done as an insider. Some changes are best initiated from within the belly of the beast.” (Hill Collins, 2013, Pp.38). Which intuitively makes sense, shifting the practices and beliefs can most easily be shaped from within. Though, I’m coming to the belief that perhaps this may not be true of teaching because the very conditions of the profession mean that introspection and reflection are perhaps not the most feasible or reasonable things for teachers to do, and even less so things to be expected of them.

To counter this, she notes, “Both forms of truth telling are intertwined throughout my intellectual career, with my books, journal articles, and essays arrayed along a continuum with speaking the truth to power and speaking the truth to the people on either end. Engaging these two forms of truth telling within a singular work is challenging.”(Hill Collins, 2013, Pp.39) This means that a mixture of public facing and academic facing publications might be reasonable, nay, essential.

Melitta notes,

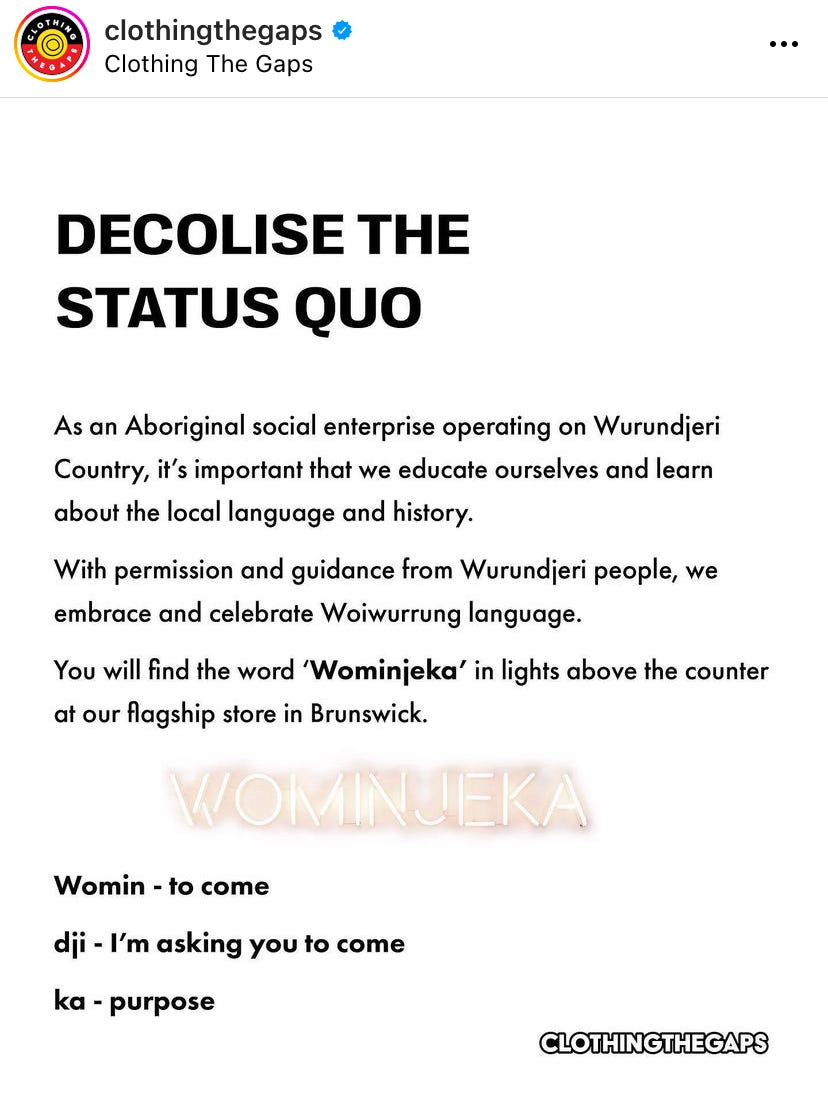

“We actively look through both a Western lens and an Indigenous lens; looking for ways to privilege our Indigeneity while revealing the taken for granted assumptions and hidden institutional constructs and bias located within the [box].” (Czuy, 2019, pp.6) This switching of lenses is something that would be of use to many within education, Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike - yet among non-Indigenous people, myself included, often what an Indigenous lens might even look like is not held knowledge. As Noel Pearson (2022) notes in his Boyer lectures, the misremembering or forgetting of Indigenous knowledge was a forceful and important part of the colonial project. Not as an accident, but as something that directly supported and perhaps was required for the process. It’s for this reason that a genuine interest and willingness to explore Australian Aboriginal culture is key to unpinning some of the elements of colonialism and how we manage within education.

Lakoff & Johnson (2008) outline that metaphors are containers for our thinking, implicitly and explicitly signaling our beliefs. Wegner & Nückles (2015) apply this thinking to explore students' understanding of learning, looking for patterns in their approach to study and learning. The studying of metaphors is a meaningful way to unpick our thinking, as the vast majority of metaphors come to us without context or understating. The few exceptions being those that we create ourselves, which are most worthy of study, for not being ingrained in our consciousness, but wrought fresh from modeling clay.

Kori notes that, “like closing the Western eye, equity is better created. Without this critical focus on the marginalized perspective, especially with mathematics, translation into the Eurocentric worldview is automatic because this worldview is often taught as standard and

"universal" (Czuy & Hogarth, 2019. pp.7) This reiterates the automaticity of our dominant worldview, we must unpick this thinking and pattern to reach something new and positive for our society.

As Melitta notes,

“It gave me space and time to find my place; my niche on the periphery, giving me the confidence to chip away at those corners.” (Czuy & Hogarth, 2019, Pp.7). We need to start chipping away at our own corners if we are to find a meaningful niche of our own.

References

Hill Collins, P. (2013). Truth-telling and intellectual activism. Contexts, 12(1), 36-41.

Czuy, K., & Hogarth, M. (2019). Circling the square: Indigenizing the dissertation. Emerging Perspectives: Interdisciplinary Graduate Research in Education and Psychology, 3(1), 1-16.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers.

Hogarth, M. (2020). A dream of a culturally responsive classroom. Human Rights Defender, 29(1), 34-35.

Hogarth, M., & Czuy, K. (2021). Walking Many Paths, Our Research Journey to (Re) present Multiple Knowings: Creating our own spaces. Engaged Scholar Journal, 7(1), 159-182.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2008). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago press.

Pearson, N. (2022) The Boyer Lectures 2022. ABC Audiobooks.

Wegner, E., & Nückles, M. (2015). Training the Brain or Tending a Garden? Students' Metaphors of Learning Predict Self-Reported Learning Patterns. Frontline Learning Research, 3(4), 95-109.

Running word count: 91,324